This is the first installment of a three-part series on game theory.

July 07, 2021

By Rachel Smith

I could explain game theory to you, but film director Rob Reiner has already done such a good job. In his 1987 epic fairytale adventure, The Princess Bride, actors Wallace Shawn and Cary Elwes demonstrate classic game theory as Vizzini and the Man in Black. The Man in Black has poisoned one of two glasses of wine, and Vizzini gets to choose which goblet to drink from.

“But it’s so simple!” says Vizzini. “All I have to do is divine it from what I know of you. Are you the sort of man who would put the poison in his own goblet or his enemy’s? Now, a clever man would put the poison in his own goblet because he would know that only a great fool would reach for what he was given. I am not a great fool, so I can clearly not choose the wine in front of you. But you must have known that I was not a great fool. You would have counted on it, so I can clearly not choose the wine in front of me.”

This “divining” goes on for several minutes, and it’s a perfect example of game theory. Game theory is the study of interactive decision making, where the outcome for each participant depends on the actions of the other participants. When choosing a strategy in game theory, you have to consider the choices of others, and understand that they, in turn, are taking your choices into account.

At the end of Vizzini and the Man in Black’s encounter, we learn that they are not playing the same game. Vizzini believes he is playing a game which he could win or lose, but he’s not. The Man in Black secretly poisoned both cups because, as we later learn, he is immune to the poison. Cheating brings us to a level of game theory beyond my mathematical capabilities, so instead, let’s go back to the beginning.

Game theory can be applied to any number of things—economics, politics, biology—but is itself a branch of applied mathematics. It began in the 1920s with the work of John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern. They studied mostly zero-sum games, meaning that the interests of the players are strictly opposed.

Tic-tac-toe and chess are examples of zero-sum games. They are both games of perfect information, meaning that each player knows everything that is happening in the game at all times. Compare that to a game like poker. Poker is also a zero-sum game, but it is a game of imperfect information. Each player does not know the possible moves of their opponent because they cannot see their cards.

In the 1940s and 1950s, mathematicians like John Nash were applying game theory to more realistic cases in which participants might have a mixture of common and competing interests and in which there could be any number of players. The quintessential example of game theory framed at that time is still used today to explain how game theory works—the prisoner’s dilemma.

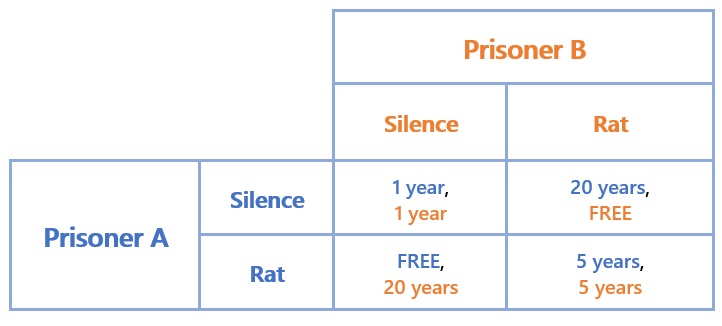

Imagine that two people are arrested for a burglary that they committed together. If neither of the prisoners rat each other out, they will both get one year in jail. If prisoner A rats on prisoner B, prisoner A goes free while prisoner B gets 20 years in jail. Similarly, if prisoner B rats on prisoner A, prisoner B will go free while prisoner A serves a 20-year sentence. Finally, if they both rat on each other, they each get five years in prison.

Game theory gives us a way to figure out prisoner A’s best strategy. At first glance, it might look like prisoner A should stay silent, because if his partner also stays silent they each only get a year in the slammer. But remember that game theory is about thinking about what the other player is thinking about. If player B thinks player A is going to stay silent, he could be tempted to rat him out and walk free.

This is where we turn to math. If player A stays silent, he’ll either get one year or 20, for an average of 10.5. If he rats his partner out, he gets no years or 5, for an average of 2.5. Mathematically, it makes sense for the prisoner to rat on his partner.

The prisoner’s dilemma is a great example of how game theory works for us non-mathematicians. It doesn’t take long for the math behind game theory to get very complex. Imagine what happens if a game is not played only once. Most “games” in real life do not involve drinking poison from a cup. We live on to play another round.

What happens when you consider that your opponent will look at what you did in round one and use that in determining their strategy for round two? What happens when there are infinite rounds? What happens when players have both common and opposing interests? What happens when there are more than two players?

Game theory is used to help people, teams, and entire nations develop strategies in any number of scenarios. Consider two nations with a boundary dispute. Both entities want a certain parcel of land for themselves (opposing interests), but they also want to avoid a war (common interest).

Consider a gas company deciding what price to set for their fuel. If they keep the price high, they will make more money, but only until a competitor sets a lower price and they start losing business. But if they lower their price, will the competition follow suit until nobody is making a profit?

Or consider an auction. Game theory has been applied in auction markets to help determine how bidders will act and predict probable outcomes. Game theory must consider the value of the item. It must also consider how much each individual values an item. But is there an equation that can take into account bidders being slightly intoxicated? And how such intoxication makes a bidder sure that she needs a large metal frog playing the saxophone as a house decoration? I’m asking for a friend. Which brings me to my next section.

While game theory is a valuable tool in determining courses of action in all kinds of situations, it is based on the premise that all players are acting rationally. You do not need to have bid hundreds of dollars on a large metal frog sculpture (because, ha-ha, who does that?!) to know that humans are not entirely rational creatures.

We have mentioned Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky before. They are the researchers who collaborated in the 1970s and introduced behavioral economics: the idea that humans do not behave rationally when making economic decisions. Mathematically, a 95 percent chance of survival and a 5 percent chance of dying are the same thing, but our human brains do not interpret it that way. If people were rational, the lottery wouldn’t be a thing.

Game theory is an excellent framework for helping us make decisions. It prompts us to think about all of the different possibilities in a situation. It also urges us to dig deeper into an individual’s motivations; to think about what they are thinking about. Sounds useful for sales professionals, doesn’t it? It is! But you’ll have to wait until next week to learn more about that.

Do you want to dig into how game theory can help you hone your sales skills? How question trees can prepare you for all possibilities? Contact us at mastery@maestrogroup.co.

Get the Maestro Mastery Blog, straight to your inbox.