This is the first post in this spring’s company-culture series. If we believe Socrates that “the beginning of wisdom is the definition of terms,” we may have a problem.

April 09, 2025

By Rachel Smith

Researching for this week’s post had me thinking about riddles in children’s joke books. You know the ones.

Riddle: If you have me, you’ll want to share me. If you share me, you’ll no longer have me. What am I?

Answer: A secret!

Here’s another one.

Riddle: I am the strongest predictor of employee attrition, but nobody can quite define me. What am I?

Give up?

The answer is company culture, but the true riddle lies in trying to define what it is and, even more importantly, how to ensure it’s working in your favor.

Let’s begin by looking at an organization with amazing company culture. Employees are encouraged to take part in educational programs. Major efforts are put forth to ensure equality between men and women as well as those of different socio-economic backgrounds. The company defines a base wage as what is necessary to thrive and not merely subsist. There are summer parties, awards for the best suggestions, and even on-site sports facilities for employees.

Would you be surprised if I told you this amazing company culture was being fostered back in the late ‘90s? What if I told you that by “late ‘90s,” I’m referring to the 1890s? While the concept of company culture gained prominence beginning in the late 1980s, obviously company culture itself existed long before then. And there were even company leaders who understood its importance. Two of those leaders were George and Richard Cadbury of Cadbury Chocolate fame.

A century before people began researching what aspects of company culture make employees more or less likely to leave, the Cadbury brothers were doing everything right because they thought it was the right thing to do. The Cadbury family’s Quaker beliefs played a large role in how they ran their business.

George and Richard Cadbury weren’t opposed to working on the factory floor along with their employees when needed. They established pensions and sick leave and offered free medical and dental care. Cocoa itself was considered a “social good” because it was a temperance drink (non-alcoholic), and chocolate was considered nutritious. That’s the story I’m going with when I stuff Cadbury Crème Eggs into my mouth this entire month—I’m doing it for the community and my health.

Back in the ‘80s (this time I am referring to the 1980s), researchers from the University of Rochester determined six main reasons why people work.

Later research found that high-performing company cultures maximize 1–3 and minimize 4–6. In fact, by asking questions about each of the motivations, researchers can measure an employee’s total motivation, or ToMo.

And why should you care about ToMo? Sales associates with a higher ToMo earn 30% more in revenue. It’s not only employees who are impacted by ToMo, either. It’s also tightly linked to customer experience and satisfaction. Finally, the link between higher ToMo and higher company success has been shown across a range of verticals, including hedge funds, fast food, retail, banking, and telecommunications.

You can even think of culture in terms of total motivation. “Culture is the set of processes in an organization that affects the ToMo of its people.”

So, culture impacts total motivation, but we still haven’t defined what we mean by culture. The fact is that even those researchers studying company culture don’t agree on a single definition. Oft-cited research from 2013 defines it as, “the set of values, beliefs, and behavior patterns that form the basic identity of an organization.” Another study published just last month in the International Journal of Human Research and Social Science Studies defines it as, “the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from others based on shared values, beliefs, and assumptions about how to behave, interact, perform, lead, and make decisions.” Collective programming of the mind sounds sort of cultish to me. I prefer Gallup’s much simpler definition of company culture: “how we do things around here.”

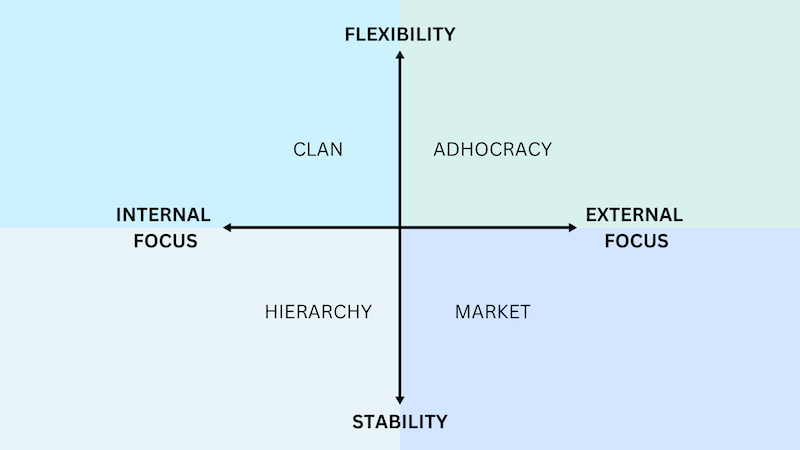

If you think there are a lot of definitions of culture, just wait until you see how many ways there are to categorize your organization’s type of culture. A commonly used framework for understanding culture types is the Competing Value Framework. On the x-axis, you have whether an organization is more internally focused or externally focused, while on the y-axis, you have whether the organization is more flexible or controlled. Based on these two axes, your company culture can fall into one of four categories.

If four is not enough for you, worry not. There are other frameworks with 8, 9, 11, or 12 culture categories. What I like about the Competing Value Framework is that it provides a good illustration of how cultural growing pains can occur. Most new startups, not surprisingly, fall into the Clan Culture category—internally focused and very flexible. You have a small group of people all working toward the same thing, and there is a lot of flexibility, as that’s the environment in which new ideas and ways of doing things are born.

Of course, startups want to keep the flexibility part of their culture as they grow and scale. But we also know that scaling your business requires some amount of process adoption. We often see this as companies go from having founder-led sales to hiring salespeople. Adopting a consistent sales process is critical, but the rest of the organization has to figure out how to interface with this new, often faster, but also more standardized sales approach.

Can you keep your culture and scale? When does culture need to change? How can culture change? Is it really worth putting resources behind company culture? Can cultural fit ever be a bad thing? These are the questions we’ll be asking and answering in our ongoing culture series. Until then, here’s another puzzle to ponder.

Riddle: When people feel connected to me, they are 4x more likely to be engaged at work, but you still can’t quite define me. What am I?

Answer: You got it—company culture. If you’re feeling out of sorts over the lack of a universal company-culture definition, might I suggest Cadbury Crème Eggs? They are delicious and good for society. The Quakers said so.

How was your Q1? Reach out to learn how we help organizations accelerate sales. We’re at mastery@maestrogroup.co.

Get the Maestro Mastery Blog, straight to your inbox.