There are so many productivity apps out there, but you can determine what to work on, and how, using some surprisingly low-tech solutions.

January 31, 2024

By Rachel Smith

When we think about all the work we have to do and how to better keep track of and organize it, it’s easy to get sucked down a rabbit hole of productivity apps. There are apps for to-do lists, apps that help you stick to habits, and apps that block other apps from distracting you. When did an entire industry spring up around the idea of productivity?

Economic growth began in 1600, according to a paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, and it hasn’t let up since. Benjamin Franklin is often credited as creating the first to-do list in 1791. By the 1850s, day planners were rampant. Productivity consultants cropped up in the early 1900s, and after World War II it was realized that women could also be productive (I know—I’m just as shocked as you are!). Computers, the internet, smartphones…and here we are today trying to decide which new productivity app we should download.

Structuring your work to increase your productivity, however, doesn’t have to be that complicated. All you need, is paper, something to write with, and a tomato.

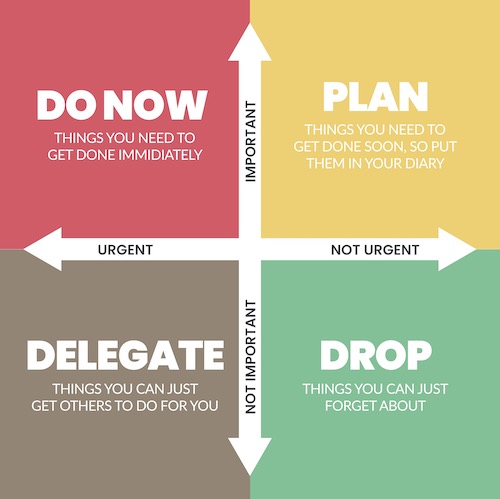

One of the hardest decisions to make is what work to do in the first place. It seems that we all have too much to do and not enough time to do it, which is why it can be difficult to figure out what you should be working on right now. A good way to determine what needs your immediate attention is by using the Eisenhower Matrix.

Here’s how it works: Draw a square with four quadrants. Your x-axis goes from urgent to not urgent, and your y-axis goes from not important to important. Now, for each of your tasks, ask yourself whether it is important, and whether it is urgent. Each task now falls into one of four categories on the matrix.

The tasks that are urgent and important are the ones you’re going to do right now. I mean, it would be great if you finished reading this first, but when you’re done, get to those tasks. An activity that is important but not urgent should be scheduled—and ideally, you should get to it before it becomes urgent. Tasks that are urgent but not important? Those you should delegate to someone else. They need to be done right away, but they don’t require your unique skillset. Finally, there are some tasks that will be deemed neither important nor urgent…so why are they on your task list in the first place? These are the activities you can get rid of completely.

There are people who find the Eisenhower Matrix to be overly simplistic, but that simplicity is part of what makes it effective. The approach is named for Dwight Eisenhower, who used this method. He was only the General of the Armies, Supreme Commander of the Allies, and then President. So, you know, maybe you’re busier?

Once you’ve used the Eisenhower Matrix to figure out what you should be working on, it’s time to get working, but how?

In 2017, the Draugiem Group in 2017 studied the habits of their most outstanding employees to see if they could uncover their secrets to success. Their research revealed that what the most productive employees had in common was that they took more breaks. When we work on a task for more than an hour without a break, our productivity starts to suffer.

The Pomodoro Technique is a simple tool you can use to break up your day into task-focused work separated by short breaks. Pick a task. Set a timer for 25 minutes and use the time to work on that task. When your timer goes off, take a five-minute break. That’s one pomodoro. After you have done four of them, you’ve earned yourself a longer, 15–30-minute break.

The technique was created in the 1980s by then-university student Francesco Cirillo. His timer happened to be in the shape of a tomato (“pomodoro” in Italian) and hence the name. Your task time and break time might vary slightly, but the task time should not be more than an hour at a stretch, and the breaks are best when they are true work breaks (as in leave your desk, take a walk, no checking email).

Let’s say that you finish a task in 10 minutes. Does that mean you get a 20-minute break? Nope. Once your tomato is set, you must abide by the tomato. It’s a great time to get in some of your 40/20 work!

You now have two easy, effective tools for enhancing your productivity and efficiency. This third suggestion is not a tool, but rather a recommendation to stop doing something. You need to hear the truth. This is an intervention: you are bad at multitasking.

I know what you’re going to say. “Not me. I’m actually good at multitasking.” But you’re not. How do I know this? NOBODY IS GOOD AT MULTITASKING!

First, let’s talk about your performance when multitasking. Study after study has found that people who multitask take longer to complete tasks, and they are committing more errors while completing them. There are three systems in the brain involved in executive control and sustained attention. They work together to focus our brains on the task at hand, select the information that is relevant to the task, and reorient us if we get distracted. When we try to multitask, there’s information that’s relevant to one task, but irrelevant to the other—too many balls are in the air at once. Your brain systems are overwhelmed and less efficient.

It gets worse. When people who do a lot of media multitasking were tested on doing a single task, they performed worse than those that don’t multitask as often. High-media multitaskers (based on the Media Multitasking Inventory, which measures how often people use more than one type of media at once) also perform worse on both short-term and long-term memory tasks. You’re not just bad at multitasking—now you’re bad at tasking, period!

So, why do we think we’re so good at multitasking? According to Daniel Levitin, neuroscientist and author of The Organized Mind, technological multitasking essentially rewards the brain with dopamine for losing focus and constantly searching for external stimulation. Dopamine feedback loop; lots of energy; a sense of wellbeing; sleep problems. Who does that describe? Heavy multitaskers. Who else does it describe? Cocaine users.

I’m talking to myself here as much as I’m talking to you (about the multitasking, not the cocaine). I currently have 44 tabs open on my browser. I counted—that’s not an exaggeration. I keep tabs on Slack and email at all times. I’ve been working on this blog “all day” because I’ve also been concurrently working on 10 other tasks as well. Am I proud of it? No. Do I know it’s not good for me? Yes. Do I know how to stop? Absolutely not.

Maybe tomorrow I’ll order myself a tomato timer on Amazon. It’s one of my 44 tabs.

If you want to learn more about setting yourself up for success, take Maestro’s self-paced learning module (and don’t check your email while you’re doing it). Find out more about our other offerings by contacting us at mastery@maestrogroup.co.

Get the Maestro Mastery Blog, straight to your inbox.