Diversifying a company culture isn't just about hiring—it's about evaluating, measuring, problem-solving, and partnering with wider networks.

August 18, 2021

By Rachel Smith

Just in the past couple of years, increasing numbers of companies have committed to hiring more individuals from under-represented groups. Many of them have added a Chief Diversity Officer position to their C-suite. Not only is this the right thing to do, but it has proven to create more competitive companies.

Businesses that are inclusive and diverse outperform those that aren’t in innovation, retention, talent recruitment, and profit. There are loads of studies and statistics to back this up. We’re not here to explain why diverse is better, though, because that’s old news at this point.

We want to talk about why, despite hiring diversity and inclusion experts and committing to hire more people from under-represented groups, the needle on workplace diversity hasn’t moved much at all. Why is that? And what can be done about it?

If hiring alone was going to solve the lack of diversity in the workplace, many companies would build a workforce that directly reflects the diversity of the U.S. population, from entry-level positions all the way up to the executive team. The issue is that there are so many things that have to change before and after hiring in order to attract and retain employees from under-represented segments of the population.

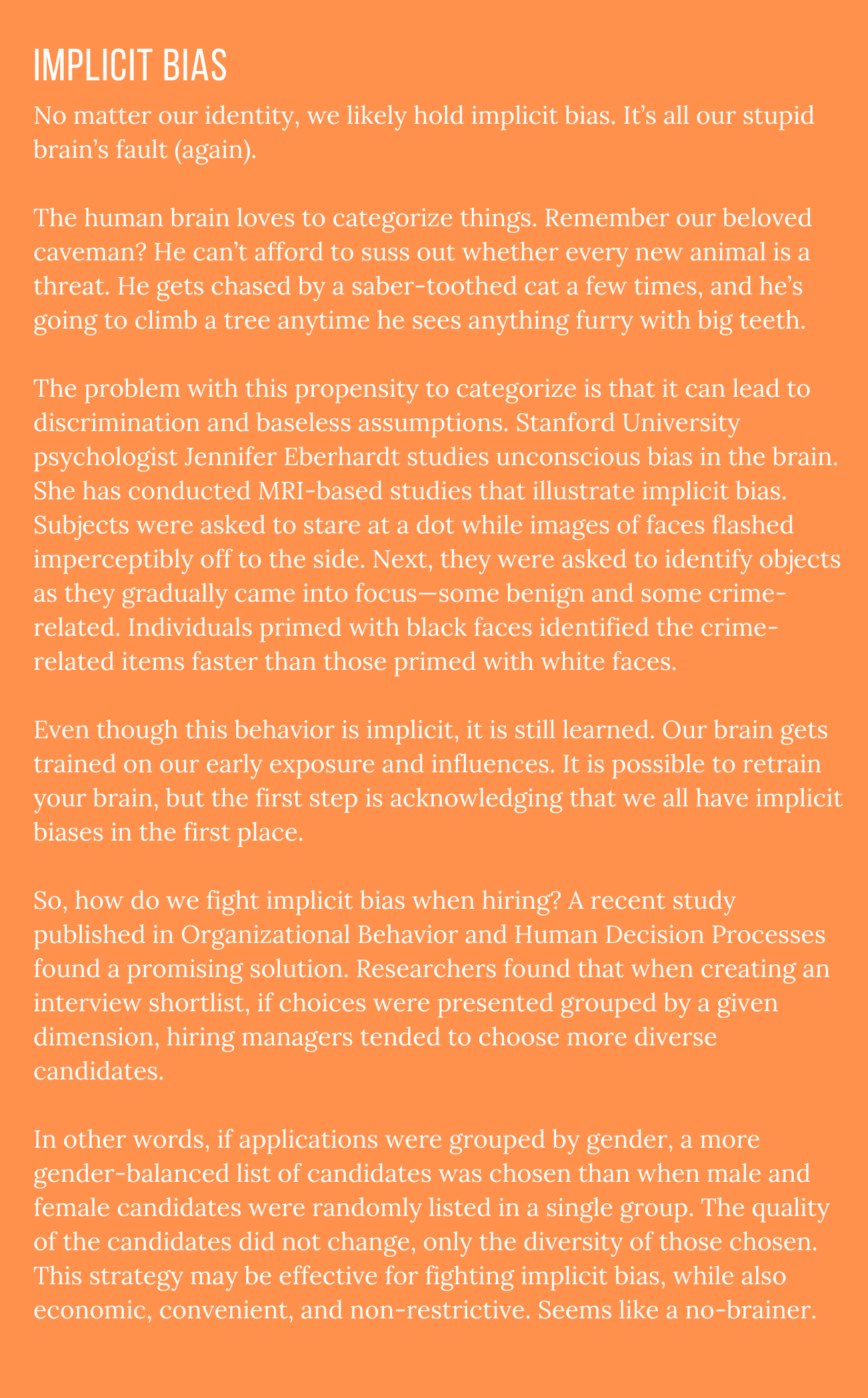

Your organization likely has a hiring process in place that is used when searching for new talent. Where you post your job, the language in the job description, and even who is managing the hiring process all impact who applies. Creating a hiring goal for diverse talent without addressing areas of implicit bias in your recruiting process will not attract additional highly-competent, diverse talent.

Increasing the diversity of your workforce is a good first step, but you still need to take a closer look at your company as a whole. Are you diverse in all departments, or just a few? Is your C-suite becoming more diverse as you hire from more under-represented groups, or has it stayed the same?

How long an individual stays and what their upward mobility will be both depend on your company’s processes and culture. If you have been a largely homogenous organization for some time, your processes and company culture may have been built for one group. Again, there is likely implicit, or unintentional, bias that favors one group over another.

The journey to a more diverse and equitable work force is a long one. At Maestro, we like our workshops and content to provide immediately actionable take-aways. The following suggestions won’t get you to your final destination, but they are great places to start as you embark on your journey.

Your company’s goal to increase diversity can’t be an add-on to everything else you do—not if it’s going to be successful. Instead, diversity and inclusion goals need to be woven into all parts of your business. The commitment to attract more under-represented minorities should start with the CEO and be infused throughout the organization.

I really love Ijeoma Oluo’s definition of racism in her book, So You Want to Talk About Race, and it helps explain why inclusivity has to be infused everywhere in order to be effective. According to Oluo, “Racism is any prejudice against someone because of their race, when those views are reinforced by systems of power.”

One-off diversity initiatives don’t work because the bias has already been baked into the pie. If you hire for diversity but don’t make any other systemic changes, you’re only addressing the first half of the definition.

When you set a new goal for your business, whether it’s shortening your sales cycle or increasing your number of cross-sales, how do you know whether you’ve accomplished your goal? You measure it. You develop KPIs. Approach your goal of increasing diversity like you would any other business objective.

You won’t know how successful you’ve been if you don’t know what you’re starting from. If you don’t have a benchmark, you won’t know what your objectives should be. Inclusion-related KPIs should be treated just like any other KPI. Not only should progress (or lack of it) be measured, but employees should be held accountable just as they would be for any other business objective.

Measuring equity and inclusion through KPIs also helps with another important strategy—you need to figure out exactly where there are issues. Are you attracting under-represented populations and hiring them, but they aren’t staying very long? Maybe your progress looks great for entry-level positions but less so at the executive level.

Pinpointing where the problems are will inform you where to make changes. It also prevents you from thinking your journey is over before it is. You might look at your overall company population and find a huge increase in diversity, but if it’s all in lower-level positions, there is still more work to be done.

You have figured out how to advertise for open positions or contact the right people in your network to attract great individuals. Now you have a different goal—attract great individuals from underrepresented populations. This doesn’t mean you have to give up on the job sites which you have historically used. It just means you need to use other avenues as well.

Post positions in more places. Post positions on niche job boards. Reach out to organizations that specifically serve under-represented populations. Intentionally seek diverse referrals. You can’t hire more under-represented minorities if they don’t apply.

Did you know that there are 25,000 terms that can convey an unconscious bias toward men or women? Don’t worry, you don’t have to memorize all of them. The words you’re using in your job descriptions, however, could be dissuading certain groups from applying to a position without you even realizing it.

Audit your job descriptions to remove any implicit bias. There are a number of tools online that can help you assess your wording. You don’t have to completely avoid gender-conveying words—just make sure there’s an even balance. Asking for input from others and doing some research on coded wording can help. On the other hand, studies have shown that adding language about diversity and inclusion does not actually help in getting more under-represented groups to apply.

Adopting a standardized hiring process with objective hiring criteria can help eliminate the human tendency to favor the in-group. Everyone should be asked the same questions. Creating scorecards on which you rate prospective hires also helps maintain objectivity.

It can be difficult not to improvise during interviews, especially if you know a candidate or they were referred by a friend. A standardized process doesn’t mean that you can’t interact normally with a candidate, it just means that your assessment of each individual should be based on a structured interview. Structured interviews have also been found to be better at predicting job performance—an added bonus.

Having someone from an under-represented group lead your search committee can have a large impact on the diversity of your applicants. Studies show that when a search chair is from an under-represented group, applications from candidates from under-represented backgrounds goes up by 118 percent. Another study found that when a woman leads a search committee, 23 percent more women apply to the position.

A diversified interview panel is important for all potential hires to see, not just those from under-represented groups. Millennials are making up more and more of the workforce, and 47 percent of them are actively looking for diversity in the workplace when they consider potential employers.

If you do decide to call on under-represented group members to lead a search committee or provide input on your evaluation method, it’s important to be cognizant of the burden you’re placing on them. Diversity initiatives should not fall on the backs of those who are suffering from lack of representation in the first place. Consider some sort of compensation for the extra work being done.

Every job description lists qualifications that the candidate should meet in order to be considered. Women are less likely to apply for a position for which they don’t meet all of the qualifications than men are. But in reality, only 28 percent of hiring managers expect applicants to meet every qualification. By overstuffing the qualifications section, companies are inadvertently skewing their applicant pool toward men.

It is also useful to look critically at how hiring teams rate resume information, and whether some of these tendencies can skew hiring away from certain groups. Many companies, for example, put a lot of weight on prestigious internships. A lot of internships, however, are unpaid. This often rules out lower-income individuals who can’t afford a non-paying job. Studies show that a paid summer job on a resume does not improve an applicant’s rating at all.

It’s essential to think about what qualifications an individual truly needs to have in order to excel in a position. Do they really need a specific degree, or does a certain level of work experience count for just as much? Is your long list of “nice-to-have” skills limiting your applicant pool?

One of the silver linings of the COVID-19 pandemic is that many people have had the opportunity to work from home—something that might not have been allowed previously in their company. As businesses realize that remote workers can effectively support their organization, it’s a chance for them to think about how this could also support their diversity goals.

Tech companies tend to be extremely geographically concentrated. In fact, 90 percent of technology-intensive innovation sector growth from 2005 to 2017 occurred in only five metro areas. By getting rid of any geographic biases, tech companies can do more to hire from under-represented populations.

There are several states that have a high “tech talent diversity score” but aren’t located in the traditional tech locations. By expanding their search geographically, tech companies can do more to move the needle on their diversity and inclusion goals.

We wrote earlier that some biases are already baked into the system when it comes to hiring. For example, when people think about potential candidates for jobs, they tend to pick candidates who match the traits of the people already in those jobs. An informal shortlist for a technology startup will likely be made up of men, because men have historically filled most of these roles.

Research published in Nature: Human Behavior reveals an interesting phenomenon. If you ask people to list three potential candidates for a role dominated by men, most people list three men. If you then ask them to list three more potential candidates, the number of females listed is 33 percent higher than in the initial short list.

More research needs to be done, but a starting point for getting more women into the male-dominated tech field could simply be to make your short list longer. Interestingly, the results work for either gender bias. When people were asked to list role models for their daughters, an extended short list was more likely to include men.

We know that simply saying you are committed is not nearly enough, and we know that diversity and inclusion cannot be tacked on as a side mission. Making improvements is going to take a lot of self-reflection—making efforts to uncover implicit bias that we aren’t even aware of and changing how we go about recruiting, hiring, and coaching employees. It’s a long journey, but at least we now know where it begins.

For thoughtful guidance on reinvigorating your organization’s hiring practices, contact Maestro at mastery@maestrogroup.co.

Get the Maestro Mastery Blog, straight to your inbox.